Last year I wrote a centenary article for a regional newspaper about the baffling disappearance of the SS Waratah. I still find it a gripping story and thought I would re-air the article for a geographically wider audience…

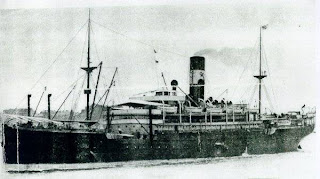

The SS Waratah, a British luxury steamer carrying 211 passengers and crew, set sail in 1909 from Durban to Cape Town and then disappeared somewhere off the east coast with all on board. Sometimes called the ‘South Atlantic Titanic’, the 465 ft ship has never since been found.

The Waratah was built in Glasgow for the British company Blue Anchor Line and was named after the emblem flower of New South Wales. It was to be the company’s flagship, serving as a passenger and cargo ship, taking European emigrants to Australia and then returning with freight.

The Waratah had a hundred first class cabins, eight state chambers, a salon and a lavish music chamber. On outgoing journeys the cargo holds could be converted into dormitories that were able to transport up to seven hundred steerage passengers. She was an immense ship, capable of carrying enough stores to survive at sea for a year, as well as having a desalination plant for producing drinking water. What she did not have was a radio, but at the time this was not uncommon.

In July of 1909, having already completed a successful maiden voyage, the Waratah was returning home from Melbourne, via the ports of Durban and Cape Town, on its second voyage. When it reached Durban, a few passengers disembarked, and one passenger, an engineer, cabled his wife in London, saying: “Booked Cape Town. Thought Waratah top-heavy, landed Durban. Claude.”

In a 17 December 1910 article in The Times Claude G. Sawyer claimed that he had had nightmares of pending disaster whilst en route to Durban and that he had been alarmed at the slow roll of the steamer, which did not quickly right itself after having been tilted by a swell. So although he was booked through to Cape Town, Sawyer decided to disembark in Durban and sent his wife the above cable. He relayed his nightmares to the manager of the Union Castle Line the morning after disembarking, and this action later helped save his reputation, as he had spoken of his fears before the Waratah’s disappearance.

The Waratah left Durban on 26 July and was due to arrive in Cape Town on 29 July. On the 27 July she passed the SS Clan McIntyre off Port St Johns and the two exchanged signals. This was the last verifiable sighting of the Waratah. Later that same day the weather worsened, creating strong winds and great swells.

The Union Castle Liner Guelph passed a ship during the storm and exchanged signals via lamp, but because of the poor visibility created by the storm, the crew could only make out the last three letters of the passing ship: “T-A-H”.

That same evening the Harlow saw a ship almost 20 km behind her, ploughing through the waves. The Harlow’s shipmate saw two bright flashes coming from the same direction, and then there was blackness. But he deduced that the flashes had been caused by brush fires on the shore, and he and the captain agreed that it wasn’t worth noting in the log. Only when they heard of the tragedy did they think that it was perhaps significant.

After the Waratah’s disappearance, there was a Board of Trade inquiry that focused on the supposed instability of the ship. Sawyer, in his interview with The Times, said that the entire journey to Durban had been uncomfortable, with the ship’s rolling reaching a 45 degree angle and more than one passenger being knocked off balance and injured.

But there were those who thought the ship stable; it had been given a “+100 A1” rating when tested for seaworthiness, and the Waratah’s design was heavily based on that of the Geelong, which had performed very successfully. And so the inquiry could discover nothing conclusive.

More than one rescue ship was sent to look for the missing Waratah. The HMS Hermes, searching in the area of the last sighting of the Waratah, encountered such strong, high waves that she strained her hull. The SS Wakefield, chartered by relatives of Waratah passengers, searched for three months, finding nothing.

Twenty years after the incident, Edward Joe Conquer, a Cape Mounted Rifles soldier, claimed to have seen a ship roll over and sink off the coast of the Transkei on the day of the Waratah’s last sighting. But many have questioned his integrity. And for his words to ring true of the Waratah, the ship would either have had to have turned around to return to Durban, or have lost engine power, as it was farther north than it logically should have been after passing the Clan McIntyre.

One of the most widely held theories of what occurred is that the Waratah was overwhelmed by a rogue wave that filled its holds and quickly sunk it. Either that, or the same wave overturned it, aided by the perhaps top-heavy nature of the ship. The latter option helps explain the lack of debris, as any persons or buoyant objects would have been trapped under the overturned deck. On leaving Durban, the Waratah had had in its holds 6,500 tons of food and lead concentrate. If a freak wave did hit it, the cargo could have been dislodged and as such would have helped to capsize the ship.

After the ship’s disappearance there were, however, two possible sightings of floating bodies near the Bashee River mouth, but neither were picked up – if they even were human corpses – and they cannot be linked to the Waratah with any certainty.

The freak wave theory gained greater prominence later in the century, redefined as the ‘hole’ phenomenon. In 1973 Professor Mallory, an oceanographer at the University of Cape Town, published a paper about the prevalence of abnormally large waves off the east coast of South Africa. He argued that the strong Agulhas current, along with the narrow continental shelf and a severe storm, could work together to create waves of up to 20 m in height, which would be large enough to swallow up a ship even as big as the Waratah.

Another theory is that there was an explosion in one of the coalbunkers, which would explain the supposed sighting of flames as witnessed from the Harlow. But such an explosion would not have sunk the whole ship without there being time to launch a lifeboat. (Unlike the Titanic, which sank three years later, there were enough lifeboats for all onboard.) And as with all the non-paranormal theories, it still doesn’t answer the question of where the wreckage is.

Other less accepted theories are that the ship was caught in a whirlpool or that an upsurge of methane sank it. In 1899 the Waikato had lost power and drifted for fourteen weeks before being recovered; many at the time speculated that the Waratah had lost power after being hit by a freak wave or having had some sort of mechanical breakdown, and that it was similarly adrift. This would explain the absence of a shipwreck. David Willers wrote a book arguing that the ship had drifted all the way to Tierra del Fuego.

The writer Clive Cussler worked in partnership with Dr Emlyn Brown, head of the South Africa National Underwater & Marine Agency (NUMA) and the foremost researcher into the disappearance of the Waratah, and the two men spent decades searching for the wreck. Since 1983 Brown led several expeditions to inspect the remains of ships hoped to be the Waratah.

In 1999 Brown announced that the wreckage of the Waratah, fitting the location described by Conquer, had finally been found. An underwater expedition was organised. But Brown had to later regretfully report that the wreck thought to be the Waratah was in fact a WWII cargo ship that had been sunk by a German U-boat in 1942. In 2004 Brown announced that he had given up the search, stating he had “exhausted all the options. I now have no idea where to look.”

One thing is clear: the name Waratah has proved to be an unlucky one. No less than four ships of the same name sank between 1848 and 1894. Yet all four of those losses have known causes. It is only the SS Waratah that remains elusive.

Reminds me of Ship of Gold - story of the USS America I think it was called. A side wheel steamer which sank off the East coast of the USA carrying 18 tons of gold. A brilliant story of how it was eventually found. I wonder what else apart from food and lead was on board?

ReplyDeleteHey Japes. I just googled it - very interesting! You were right - it was called the SS Central America. One site said it was the worst peacetime sea disaster in American history. Those who were in the discovery group must be pretty wealthy now!

ReplyDeleteI hope to resume my search for the legendary SS Waratah if I can find the available sponsorship to resume my search.Anyone may corrospond with me if they wish to.Emlyn Brown emlynbrown@gmail.com

ReplyDeleteI wish you all the best!! It would be such a wonderful discovery.

Deletethe science behind the sinking of the Titanic led me to think about the Waratah. Ships of this era were constructed of steel high in sulphur, which made the steel brittle, inclined to snap rather than 'bend' in cold conditions, subjected to significant forces. W was alleged to have taken a knock at Kangaroo Island off Australia, or else even a scrape along the sandbar at Durban harbour, compromising rivets in the horizontal plane. One or more may have even opened breaches less than an inch in diameter (as in the case of the Titanic). W was running eight hours behind schedule on her voyage to Cape Town which may in part been due to the storm but also because she was taking on water. Captain Ilbery may have believed that with the double hull, air-tight compartments and twin engines, it was manageable. He may not even initially been aware of the problem if the breach was limited to one air-tight compartment. However, the forceful winter swells and waves may have caused the compromised rivets to 'pop' opening a significant breach in a zipper-like effect, flooding one or more of the air-tight compartments fore in the ship. This over and above any issues of a high meta-centre, would have made the front of the ship start to sink much like a submarine, under power. When the magnitude of the disaster came to the attention of the captain, it was probably too late and all they managed to do was fire two gunshots, seen by the Harlow as flashes, as a desperate attempt to signal distress. W would then have dived and at a certain depth the engines were sure to have exploded, scattering wreckage over a wide field, difficult to detect by sonar.

ReplyDelete